Senior designer and project leader Adriaan Kok (1973-2024) was one of the designers of the Hovenring. In this interview by Diane Daniels, he told her all about the challenges involved.

What was the goal of the Hovenring and how did you address it?

There were many. The original intersection was a big roundabout used by all modes of traffic that was terribly congested and not well designed for cyclists. Eindhoven recognized that this junction was an important crossroads, joining with Veldhoven and Meerhoven; was on the way to the airport; and was near the A2, the country’s most important north-south highway. Also, the city focuses on innovation and technology and is known as the City of Light, as it’s the birthplace of Philips. Eindhoven is really aware of its city branding and wanted this bridge to be innovative, to use light creatively and to fit in visually with existing local landmarks such as the Evoluon, a futuristic saucer-shaped building up the street.

Where did the idea to build a suspended roundabout come from?

First, we did what we always do – getting the requirements of everything involved. We sketched and designed various alignments to figure out what would be the most efficient and comfortable and cause the least hindrance for existing traffic. We came to the conclusion that an elevated roundabout with four connecting bridges offered comfortable and direct routes and could be built within the existing roundabout area below it. This offered us the chance to create a flying saucer like design that elegantly refers to the Evoluon building. As the idea grew, people got more and more enthusiastic.

How did you figure out the technical components to make it work?

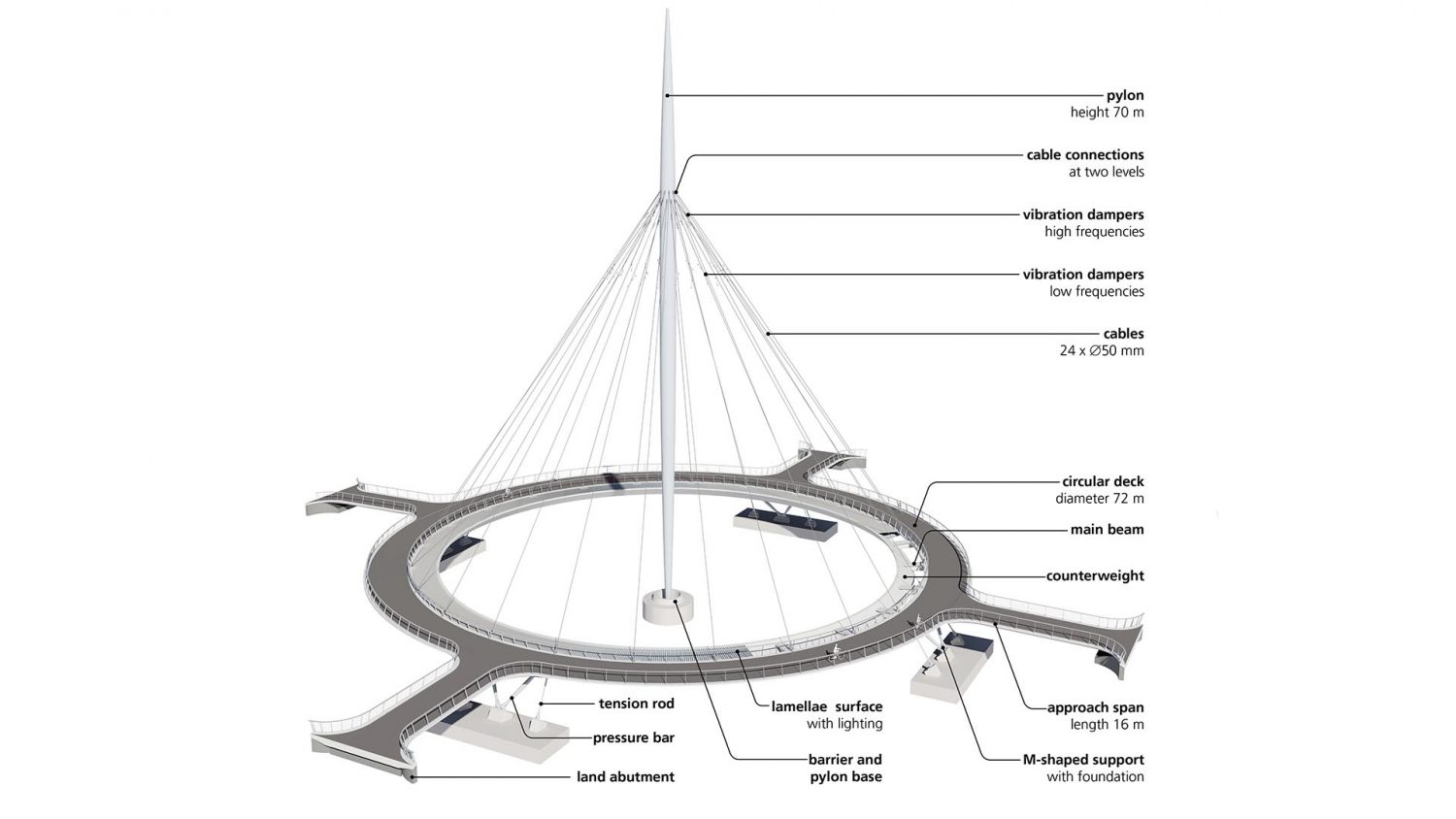

There were many technical challenges. For the bridge itself, we wanted an efficient structure with a thin, circular bridge deck. In essence, we were looking for a clean and simple concept of just a circular deck and a central pylon. By only attaching stay cables to the inner side of the bridge deck, where it connects to a circular counterweight, torsion within the bridge deck is limited. The ring on the inside is partially filled with concrete, which acts as a counterweight and balances the bike deck. So on the outside you have bridge deck and on the inner side you have stay cable and counterweight, which balances the deck around the stay cable. It’s a well-balanced and efficient structure, which significantly reduces the amount of steel needed. Cost wise that’s also a good thing.

Overall, I don’t think a structure like this one has ever been built before. Convincing all stakeholders and disciplines involved of the fact that this new design was efficient and could meet all the requirements was a challenge but we succeeded. I am proud that we made it happen.

Another challenge was spatial integration. The existing infrastructure and buildings set the boundaries for the grades of the slopes leading up to the roundabout. As space was limited, it was decided to lower the ground level of the intersection underneath by a meter and a half, allowing for a comfortable slope for pedestrians and cyclists.

Also, on the ground, we needed to place the central pylon in the middle of a very busy crossing. I had the impression it would be possible but we had to ask the Eindhoven traffic planner. Luckily and to my happy surprise, he agreed with me.

The lights around the structure are really spectacular. How did you decide where to place them?

We realized that the space in between bike deck and counterweight was a logical place to put lighting. We filled that gap with translucent sheeting and tubular lights, creating a ring of light that also would fit in with the urban planners’ goal of creating a special lighting effect. At night the ring of light is clearly visible. Together with the illuminated pylon, the lighting certainly lives up to the City of Light name.

Aside from design and technical puzzles to solve, what other challenges did you face?

I would say the development process. We were working with different disciplines within the city, such as traffic planners, maintenance, urban planners, as well as local stakeholders – businesses and residents. For me, it’s most important for people to feel co-ownership. Like the traffic planner of the city of Eindhoven, who concluded that it was OK to put the pylon right in the intersection’s center, he’s now a very active promoter of the Hovenring. With the local advocates, there was a lot of doubt and fear about the grades of the ramps. We actually invited them and other stakeholders involved on a little bike tour around Eindhoven to ride up different ramps and bridges – we didn’t tell them ahead of time what grades they were, but we’d measured them first. To everybody’s surprise, slopes that were thought to feel steep actually didn’t. So not only were people happy but they felt like they were part of the process. The Hovenring gradients are all a little different, but range from 2 to just over 3 percent.

Soon after the pylon was placed during construction, significant cable vibrations were noticed and you had to make adjustments. Was that a disappointment?

Not at all – we planned for that in the budget. Cable vibrations are to be expected in a cable-stayed structure such as the Hovenring, but in general are very hard to predict. We had set aside money in the budget to address the issue should it occur and ended up using less than we’d budgeted for. The solution was to use two types of dampers, high frequency and low frequency. By attaching them to the cables, it gave a counter vibration, solving the problem.

The Hovenring opened to great fanfare in the summer of 2012, and was immediately well used by residents. But the surprising attention was that photos and stories of the bridge went viral online and the Hovenring became an international sensation. How did that happen?

For some reason National Geographic discovered it and they sent a photographer, who made a beautiful picture. That photo went viral within the bike community. Later, when I did a presentation at Velo-city I met an influential cycling writer from England who wrote about it. And then Wired wrote about it and it just kept going from there. One wow thing led to another. It was quite special.

In many ways, the Hovenring has become your calling card. But the design is custom and not suitable for every location. How do you address that?

Because it’s such a high-profile project, I’m often asked to tour it with people or to go speak at different destinations and events. But what I usually do in talks is start with the Hovenring and then share what I’ve learned and how we applied this to other projects. In fact the people who invite me to speak are well aware that we’ve done a lot of different projects. They consciously use the Hovenring to attract an audience, but they specifically want to also talk about other projects and how they’re developed. Each project has a unique optimal solution.

What are you proudest of with the Hovenring? Do you feel it’s your engineering legacy?

All our projects start as a fantasy in somebody’s head. So, yes, it’s amazing and beautiful that you see your own fantasy become true and that other people like it. It’s really good to read that it inspires people to think out of the box or feel that things are possible. And it’s even nicer when you can explain to them that, yes, it looks nice but it was actually an efficient synergetic solution. Those things combined are what make it so special.

One of the things I like most about the project is that it is a truly integrated and synergetic design where structural and architectural elements are part of one solution rather than a layer cake of partial solutions that don’t hinder but also not strengthen each other. This is something we always try to accomplish. When you work at it, things can complement each other and be synergistic. That’s what the Hovenring was to me.

Also, by involving everybody, we ended up with a landmark that helped city branding and is comfortable to use. It’s great when that happens – you want this for every project. It’s the perfect example of what a good process can lead to.